he knows so much about these things.

on jean cocteau's 'orpheus,' being an actual violent femme, and riding in cars with boys with steven patrick morrissey.

I got the email length warning from Substack, so make sure you hit “View Entire Message” at the end of the email to read the whole thing. Strap in, folks.

So, before I dive in, I feel like I need to write a little intro, because my subscriber base has pretty much doubled since my last newsletter edition earlier in the month — all due to my friend Andrew, who started his own newsletter and apparently has dozens of super supportive friends who also want to support me because I know him. It’s slightly overwhelming and very sweet, especially since most of the people in my life who keep up with this are either fellow writers or friends who sign up to read my rambling because they love me and know this is a better outlet than when I have nothing to do and start creating problems for myself. So! This is all very unexpected! But in a delightful way! Welcome!

For now, I’m a stranger invading your inbox, so I’d encourage you to go read my other few newsletter entries to get a flavor of what you’re getting yourself into. To give you the basics: I get paid to write about music — well, I usually get paid to write about musicians I have minimal feelings about, and I usually write about cult music figures I adore for free. I have two pieces forthcoming in different publications and there’s one of each situation thrown in there, which feels like a good balance artistically for the moment (not so good financially, but I’m working on it).

As music is such an intense part of my life, I write about my own musical passions on here a lot too. For my second newsletter of the month, I initially thought I’d take a swing at something personal: I set about to recount a very strange incident that happened the day I graduated last year, involving almost passing out due to heat exhaustion and then ending up abandoned and nearly incapacitated in the middle of the city. I have the draft of what I wrote saved for a future edition, but I think I might need to put more space between myself and the incident to be able to express it well; not only did I feel like I was just dumping my own personal issues onto everyone, like I’d trapped you all in my diary for safekeeping — meaning it’s not a fun read for you — but the writing just wasn’t that good. I think time and perspective will mold the story into something worth sharing, but also, to be brutally honest (because that’s what we do here), I don’t think it’d be a great intro to who I am and what I’m passionate about if I just handed over a this-is-your-life, matter-of-fact reminiscence of my problems.

So! We’re doing another musical deep (reeeeally deep) dive into an artist and song that have bent and reshaped my life beyond repair…and it’s a tricky one, so let’s ease into it. Let’s brush up on some of our Greek mythology, for a start.

I’d like a show of hands on how many people remember the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and I’ll assume it’s a muted response because I get it, it’s been a while since our last Percy Jackson revisit. Here are the basics: Orpheus — musician, bard and the son of Apollo — finds the dead body of his wife, Eurydice (her cause of death varies based on the version you hear, but most agree she fell into a nest of vipers somehow, which sucks and also sounds like something I would accidentally do), and mourns by playing his lyre. Protected by his demigod powers or maybe the power of music or maybe both, he descends into the Underworld to beg Hades and Persephone to let his wife come back. They are moved by his beautiful, emotive playing and take pity on him, agreeing to spare Eurydice so long as she follows behind them as they leave the underworld and Orpheus does not look back at her until they’d ascended into the living world again — maybe this is where it starts sounding familiar. Not hearing her footsteps and fearing the gods had tricked him, Orpheus looks back as soon as he’s at the threshold, and Eurydice disappears.

Orpheus returns to the mortal world and sings mournfully for the rest of his life, begging for the gods to take him next. When he’s eventually torn limb from limb by beasts (something that just happened back then, I guess), his head remains in tact and still sang as it floated across the sea.

The world’s loneliest man bobbed onward, comforted only by his the sound of his own musings, even when the rest of the world might beg him to stop — or even stop listening altogether. Huh. Let’s come back to that later.

For now, let’s fast forward to Paris in 1950, where avant-garde renaissance man Jean Cocteau films his dramatic interpretation of the Orpheus myth. Moving the story to contemporary France, where Orpheus is a famous poet rather than a musician (because “poet” used to be a real job for people who didn’t have to read bad writing while making weird hand gestures on TikTok — yes, that was a Rupi Kaur hit, no one’s safe here), the film adopts a surrealist style to depict Orpheus falling in love with one of Death’s (with a capitalized D) subordinates. They travel between the living world and some version of purgatory through mirrors; it’s all extremely French and fatalistic and gorgeous. I highly recommend watching, I think it’s still on HBO Max.

Alongside its surrealism, the film is known for its thinly veiled allusions to the openly gay Cocteau’s own sexuality. There are multiple instances in the film where he makes visual references to another Greek mythical figure — Narcissus, who, dating back to the Victorian era, has often been associated with homosexuality in literary and popular culture. Though ostensibly about heterosexual relationships, the movie’s greatest love affair is between leading man Jean Marais — who was in a long-term relationship with Cocteau at the time — and his partner’s camera. Just the framing of his face — the care put into it — says more than the language ever could. Maybe we, the viewers, are Death, gazing longingly at our statuesque medium of choice between worlds, knowing he is one of the few who could translate our terror and radiance. It does your head in if you think about it a little bit.

When writing about the movie’s basic themes in his book The Art Of Cinema, Cocteau notes one major through-line: “Mirrors: we watch ourselves grow old in mirrors. They bring us closer to death.” Like Narcissus, Marais is often seen flush against his own reflection, his face containing all of the agony and beauty and romanticism that his infatuation with Death can hold.

We see a man who doesn't dream about anything but himself. Huh. Again, let’s dog-ear the page — we’ll get back to that in a minute.

Let’s take a quick pitstop in Milwaukee, Wisconsin circa 1981 — don’t worry, we won’t be here long. Someone asks struggling bassist Brian Ritchie what his band is called, but he and drummer Victor DeLorenzo haven’t put a real band together yet. He replies, “We’re called Violent Femmes.” It’s one of the great band names of all time, but it’s not necessarily a fitting one, if you ask me. Violent Femmes would eventually find their other members, put out a great debut album and a couple pretty good albums after that, but that’s not so relevant to what we’re doing here. Just remember that name.

Now, we’ve arrived at the main event. Our final destination is May 31, 1982, the day the Pope (I have no idea which one) visited the industrial city of Manchester, England. His visit was not the most important thing that happened in that city on that day, as you may have gathered from the excessive vamping I’m doing here.

Four years prior, a Manchester native born to Irish immigrant parents (as well as a pop music obsessive and wannabe guitarist) John Maher (called Johnny, pronounced “Marr”) had attended a Patti Smith concert with a few of his older friends, one of whom introduced him to a mutual friend named Steven. Cut from the same Irish-Mancunian cloth, Steven was locally famous for his scathing record and concert reviews occasionally published in NME, his undying devotion to punk innovators The New York Dolls (as well as actor James Dean and writer Oscar Wilde) and his cripplingly introverted nature. According to a much different Steven in a much different time, the first thing Johnny said to him was, “You’ve got a funny voice” — and he certainly did, with only a hint of a Northern accent under the soft vocal timbre of his own design.

Four years later, Johnny is looking for a songwriting partner to start a band of his own after leaving school and jumping from group to group. Four years later, Johnny hasn’t forgotten that voice — or that face, which we’ll soon learn both adores and repels itself.

He knows the owner of both the voice and the face had done one-time singing stints in a band with those older friends. He knows the owner is a writer. He knows this person grew up loving the same British glam rock that he did — Bowie, T. Rex, Roxy Music. He knows he loves the American proto-punk of the mid-70s — The Stooges in Detroit, The Dolls and Patti Smith in New York — as well as the Brill Building and Motown groups from their respective cities that had inspired them — The Supremes, Marvelettes and Martha & The Vandellas in Detroit, The Ronettes and Shangri-Las in New York. He knows a friend of a friend of a friend who knows where this person lives. He insists this friend take him there after he watches a documentary about songwriters Leiber & Stoller and learns that composer Stoller heard Leiber wrote lyrics and knocked on his door to ask if he wanted to write together.

Johnny and the friend do the same at the door of one Steven Patrick Morrissey — still writing, though unemployed and apparently unemployable. Steven asks Johnny if he wants to pick a record from his box of old singles to play before Johnny explains his mission. Johnny picks a 1966 Marvelettes single, called “You’re The One.” Anti-rock rock history is made. They call their band The Smiths.

Let me say this: for all the reverence heaped onto them by music lovers (they were the ultimate music-press-hyped band, after all), I think The Smiths get a bad rap with people my age — for reasons both deserved and undeserved.

Undeservedly, I think The Smiths are painted as a band whose only fans are straight cis “sensitive” white men. “Incel” might be the word for it now, or that could be something different, I have no idea. Johnny Marr (he legally changed it to avoid confusion with fellow Manchester band Buzzcocks’ drummer, who has the same name, and to make it easier for people to pronounce) has said on multiple occasions that The Smiths “liberated the straight boy” — Marr himself has been with the same girl since he was 15, but made a point of emphasizing femininity in all he did: women were his musical heroes, he wore makeup in a way that wasn’t gimmicky, his style of guitar playing is consciously un-macho. That’s all great — even now, I wish more people would lead by his example, because his friends in Oasis kind of fucked all of that non-bro-ish (laddish, they say there) ethos up in the 90s — but excuse me if I’m less interested in liberating the straight boy than liberating everyone else. So, what about everyone else?

Growing up, every adult I knew who truly loved The Smiths was either a woman or a gay man — they didn’t “rock hard” enough for the fairly one-dimensional, lyric-adverse tastes of others I could mention. I think this shaped my perception of the band for the better, because I didn’t first hear of them through a shitty college boyfriend like so many people on TikTok seem to have done.

This is a broad generalization, but it seemed like those young male fans often eulogize how sad The Smiths songs are — which, yes, I certainly heard and related to, but I also heard how fucking funny they are, how many eye-rolls and winks are contained in a single verse of a song Morrissey’s written. I doubt there’s ever been a funnier lyricist. There was knowing melodrama — acknowledging the absurdity of all of us feeling these silly, overwrought emotions like we’re the only one to ever experience it…but we’re all feeling them, aren’t we? Isn’t that ridiculous? Even when the misery wasn’t exaggerated for effect and did toe the line of something like suicidal ideation, there was bravery in it, longing in it, heart in it. It was the refusal to lay down and die even when we proclaimed that’s exactly what we’d do. Their 70 or so songs were a bloodied, bruised burst of life — smart and contradictory and true. I don’t hear misery in that. I hear that we move because we must. I hear swords in hand.

It might be notable that marginalized groups are often forced to deal with loneliness through humor, because it’s something they have to learn to accept — which is maybe why younger members of each group within the traditional gender binary, with their socialized differences in maturity and emotional development, tend to hear the band differently in their younger years. Again, a huge generalization, but just a thought.

Another part of my endearment to Morrissey and Marr came in that I saw myself reflected in their obsession with the pop music tradition; to them, the type of label on the single mattered, what they said in the press mattered, their clothes mattered, their influences mattered big time. It was all the same stuff I live for, and it mattered almost as much as the music itself: the ephemera, what it all means in the larger cultural picture. Of course, this type of devotion to what is viewed as a disposable art form as always been considered a “girl” thing anyway — think early Beatles and Stones fans versus who leads the scholarship on both of those bands now. Teenage girls were the innovators in terms of archiving these pop phenomena, and Morrissey and Marr knew and know this.

Gender expression and queerness are an essential part of the band’s work, and to get to that, we have to get through why they might deservedly get some flack now.

Google “Morrissey sub-species.” Google “Morrissey Kevin Spacey.” Google “Morrissey Weinstein.” Google “Morrissey J.K. Rowling.” Google “Morrissey diversity.” You get the idea. In recent years, he’s become the worst. This happens — celebrities are terrible once they have money, it’s just how they are — but it’s especially heartbreaking because Smiths fans can’t help but visualize the Morrissey of 1983, trapped in amber, when they hear those songs.

There was openly socialist sentiment in the lyrics, as well as an intentional lack of gendered pronouns — though, perhaps even more importantly, sometimes there were gendered pronouns…at either end of the spectrum, both coming from Morrissey’s mouth. There was a vocal reverence for music made by Black women that no one else took seriously at the time. Most of the foundation of Morrissey’s writing lay on the figures of the “kitchen sink” movement, which often depicted working class British women as they truly lived in the early 60s (Morrissey stole lyrics directly from A Taste of Honey, a play written by a then-19-year-old girl from Manchester named Shelagh Delaney; the 1961 film has become a personal favorite of mine, also on HBO Max). There were conversations about radical feminism and vegetarianism and class issues in interviews.

The Smiths were an inherently leftist band. Yes, Morrissey suffered backlash due to his own arrogant statements about other artists in the press, but he certainly suffered due to pervasive homophobia as well, even if he refused to define his sexuality to both the music press and emerging LGBTQ+ press. To leave these ethics out of one’s understanding of the band (as Morrissey has now sought to do himself, for some reason) is to misunderstand the band.

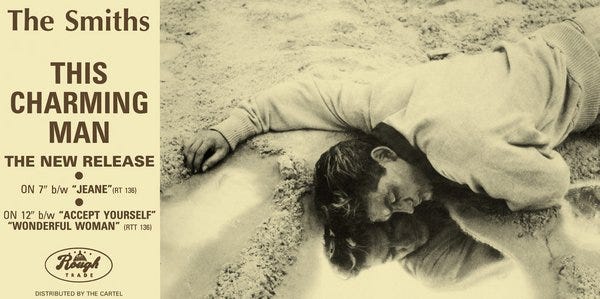

So, let’s talk about a perfect pop song that exemplifies this element of The Smiths — the otherness, the will to be subtly radical crystallized in the most accessible artistic format in existence. Let’s freeze Morrissey in 1983 with the band’s first real breakthrough song and their second single on then-flailing, now-legendary indie label Rough Trade. Let’s talk about “This Charming Man.”

Following the release of the band’s first single “Hand in Glove” (also a perfect pop song — The Smiths wrote a lot of them), the label and band made plans for a second release. Originally, the next intended single was “Reel Around the Fountain” (another perfect pop song), which ended up being the first track on the band’s debut album, but controversy had already struck; the track had gained notoriety with the British tabloids, who had totally misinterpreted the lyrics about a stilted young adult relationship that can never really last after that first loss of innocence, insisting it was about pedophilia — mostly citing the use of the word “child” in the song to back their claim up. Despite Morrissey’s vehement denial that the lyrics had anything to do with molestation, label head and founder Geoff Travis was still nervous about the commercial backlash that could come if they stuck to their guns and let it ride as the single.

Luckily for him, Johnny Marr — a year on from when he knocked on Morrissey’s door — was feeling jealous.

In September 1983, ahead of a scheduled radio session with king of British indie radio, John Peel, Johnny sat down to write a new song for the band to play during the session. Having noticed that their label mates, the much more upbeat Aztec Camera, were receiving more radio play and media attention, he decided he’d write his own version of an Aztec Camera song. He intentionally wrote it in the key of G, something he’s said he still rarely does — I can’t find the exact interview right this second, but my memory is that he said it’s “too yellow,” like, in a synesthesia way. Too sunshine-y. Of course, he wrote the musical basis of a song that was better than any Aztec Camera song to come before or since. He also wrote the music to debut album tracks “Pretty Girls Make Graves” and “Still Ill” (the latter of which I sometimes think is my personal favorite Smiths song) on the same night. Just to give you an idea of the absurd level everyone involved in this miraculous band was on at this point.

After recording his guitar parts on his personal two-track tape recorder that he could overdub on, Marr gave the demo instrumental tape to Morrissey to write lyrics over, as had become customary in their songwriting relationship. A few days later, they recorded the final product, entitled “This Charming Man,” at the session to be played on Peel’s show. Geoff Travis, who was present during recording at the BBC studio, suggested the new song should replace “Reel Around the Fountain” as the planned second single, and that the Smiths should scrap their British tour dates planned for the following week to go into the studio to record the official version with producer John Porter instead. The Smiths agreed to all of the above.

Before we move on from this step in “This Charming Man”’s journey, let’s listen to the earliest version as recorded for John Peel’s show, which later appeared on compilation Hatful of Hollow along with a couple of other Peel versions in 1984. It’s almost…I don’t want to say “folksy” (maybe my brain is just thinking “more acoustic instruments up front”), but it lolls along, yes? The feel is relaxed. Johnny and drummer Mike Joyce rest easy in their respective pockets. Morrissey’s vocal follows suit, in a way. He sings with no real immediacy, just in an alluring, almost wavering whisper. It’s gentle. Bassist Andy Rourke’s clearly Motown-influenced bassline, however, is one thing that will remain throughout each subsequent version. It’s also a reminder that Andy Rourke is an all-timer in terms of great bassists; Johnny had the flash, but Andy matched his melodic sense at every turn. Barry Gordy and The Supremes would’ve been proud. Let’s compare a little bit.

So, the following week, The Smiths and John Porter found themselves in Matrix Studios in London. It’s during this recording session that Porter, who had worked with the band’s heroes Roxy Music, suggested they insert the little stops and starts at the beginning of the first verse and after each chorus, likening it to a similar trick in Roxy Music’s debut single, “Virginia Plain.” It’s one of those tiny decisions that makes all the fucking difference in songs like this. It immediately becomes something sharper, more alive. More awake. Threatening? Startling? Maybe not yet.

The version the band records is deemed unsatisfactory for the single release. I think if I’d been there in the studio with them, that would piss me off. The London version is definitely the most reminiscent of an Aztec Camera song, which I guess was the song’s original archetype: almost dreamy in the way the guitar reverberates and lets itself lay over your senses. Morrissey’s vocal feels like it fades into the mix, again washing over whatever melody Johnny lets drift back to him. It’s pretty. I would be pissed if the pretty thing I created had been scrapped. However, as someone who was not there and who now knows where the song’s true potential lies…I agree. This was the right move. It’s certainly not their “Virginia Plain.”

Sometime in October, the band were back in their hometown of Manchester and determined at taking their final crack at the single they needed to deliver before the end of the month. Perhaps it was that stereotypical Northern environment that The Smiths held onto so dearly for their entire tenure as a band — an extra edge, an uncensored bluntness that only someone from an oft-underestimated place could deliver — that made the single version of “This Charming Man” what it is. Maybe London was too dreamy for what it needed. Maybe it was the magic in the walls at Strawberry Studios. Maybe it was just those hours of Johnny and John Porter laying down an alleged 15 guitar tracks on the final version — one of which involved Johnny dropped knives onto the strings of his Telecaster, an incident which allegedly inspired the title of “Knives Out” by Smiths-super-fans Radiohead, which then inspired the title of the movies of the same name, which is a whole cultural reference mindfuck I don’t want to get into. Maybe it was just that, in all of their mysticism and reverential worship of pop music lore, Morrissey and Marr knew what their song would become — that it would be their first taste of mainstream success. They could see it in their collective mind’s eye.

So let’s walk through “This Charming Man” as a song.

Do I need to explain that opening guitar line to anybody? Are we good on why it’s probably one of the most undeniable intros ever recorded in the history of popular music? Because that just feels self-explanatory to me — no trivia I could provide you with will get you to understand why it’s like seeing god. It feels like a razor’s edge compared to the line on the versions we heard before; still delicate, still effeminate, but not to be fucked with. Designed to get stuck in your head the second you hear it. Andy’s Supremes-y bass takes its rightful place further up in the clearer mix; I would argue it’s what propels the song to the strata of excellence and immediacy it deserves.

Our first stop/start arrives. One of the most distinctive singing voices we’ve had in music’s past four decades — often copied, never replicated — sets our scene: “Punctured bicycle / On a hillside, desolate / Will nature make a man of me yet?” Bizarre. We’ve been abandoned. Not love song material, certainly. The last line almost bites with how it assumes what you’re thinking about our flamboyant narrator, throwing it back at you with a wink. It’s simply a great opening line. Try to imagine a hit song at any other point in history that starts with something remotely like that. You can’t.

“When in this charming car / This charming man / Why pamper life’s complexities / When the leather runs smooth on the passenger seat?” I would, in this moment, like to point out that lovely vocal stretch Morrissey does the first time he sings the title, giving him space to project in a way the other versions didn’t allow. The bouncing staccato of the next line, which builds up into an equally luxurious slide into “seat,” is also perfect.

“‘I would go out tonight / But I haven’t got a stitch to wear,’” our narrator tells the titular charming man as he drives us home. “This man said, ‘It’s gruesome / That someone so handsome should care.’”

Ah. There you go. Maybe it is a love song after all.

I don’t want to sound cruel, but I always think it’s funny when people have to explain what “This Charming Man” is probably about — especially Johnny Marr. Even for Morrissey lyrics that don’t hint at any kind of romance or sexual encounter, he clearly doesn’t want to assume what Morrissey meant when he wrote anything. So as co-songwriter, he just has to kind of say that it’s not for him to say. In fact, there’s a very sweet Johnny Marr interview moment from September 1984, when they were promoting single “William, It Was Really Nothing,” where he is pressed about the meaning of the lyrics (which actually allude to a similar situation presented in “This Charming Man”). He says this:

When we first started The Smiths, I always used to think about Morrissey’s lyrics. In fact, initially, I thought it would be good to play up the ambiguity of them. But not as a new messiah of the gay movement or anything like that. I just thought how lucky was to be involved in a band that wrote gentler songs. It wouldn’t upset me if Morrissey wrote a boy-meets-girl type song, but it’s good to have songs that cater for no gender specifically. One of the reasons our records are timeless is because the lyrics are so good, and whatever gay overtones are there, I endorse 100 percent.

God, what a great quote. Just to word it like that. Again, this band was excellent at being interviewed. A few weeks before the band broke up, an interviewer straight-up asked Johnny, “Who is ‘This Charming Man’?” You can hear the smile in his voice when he says, “I’ve no idea,” and goes on to call it “a really, really flummoxing lyric.” So there you go. But, he also calls it “the start of Morrissey being a true, wonderful vocalist,” which I’ve just explained to you all.

It’s also funny when Morrissey has to explain anything he’s written. Here he and Johnny (who is desperately trying not to laugh through most of this) are on a very strange children’s TV program called DataRun in 1984. Morrissey says that “This Charming Man” is about “being charming,” which it might be…..but also, like, come on.

Anyway, after we’ve established that the stranger in the car is flirting with our narrator, Morrissey lets out perhaps the greatest “AHHHH!” committed to analog tape. Anyone who doesn’t do the yelp while doing this for karaoke is an absolute fucking coward. It’s just brilliant vocalization choice, and maybe even a major reason why that John Peel version doesn’t scratch the same itch in my brain. It’s on the London version, but drenched in echo that overstays its welcome. It’s good, but it’s not brilliance. With the minimal echo, it’s absolutely perfect — again, just sharper. A theatrical sucker punch. If Morrissey understands one thing, it’s the value of theater in popular music — what did we learn from The Shangri-Las, if not that? It also cues the moment when Johnny’s layers and layers of guitars start to parse themselves out on the chorus, remaining tangled as they weave behind him. It gets hazy for a second, but never loses the punch or focus that they might’ve lacked when the production became too heavy-handed.

“A jumped up pantry boy who never knew his place” is taken from Andy Shaffer’s 1970 play Sleuth, which was eventually adapted to the screen in a 1972 version starring Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier. It’s what the latter calls the former at one point during their feature-length cat-and-mouse game over Caine’s character sleeping with Olivier’s character’s wife. It’s probably unsurprising that many have read into its homoerotic subtext — and however you view it, it’s clear that the woman who caused their argument is unimportant by the film’s conclusion, as the two have become so much more engrossed in their funhouse mirror reflection they find the other man. Ha! Remember when I said mirrors would come back eventually?

Really, the song can be summed up in the final two lines of its chorus. It’s a punchline, maybe, but also a reassurance to whoever’s on the receiving end of the narrator’s tale. This disheveled young man who’s been abandoned and saved just learned from his savior — a savior on multiple levels: “He said, ‘Return the ring’ / He knows so much about these things.” The implication that there’s a wedding ring, and maybe a third (probably female) character who is unimportant by our story’s conclusion, ties it all up in a nice little bow. We have a new mirror to gaze into now.

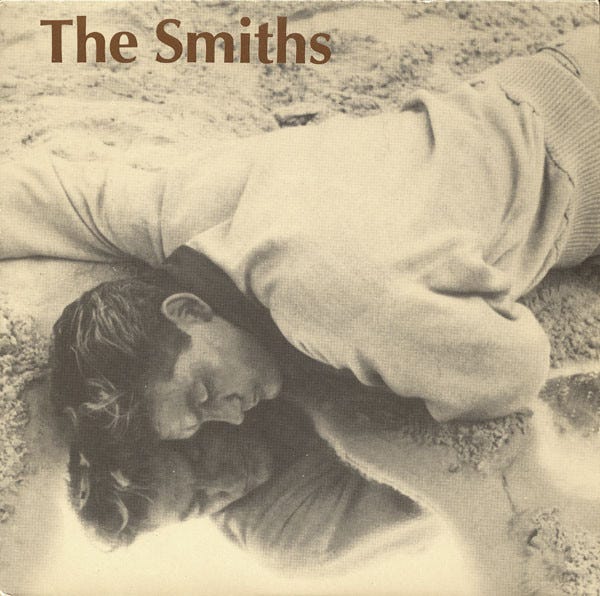

If you know nothing about The Smiths, I need to stress that the visual aspect of the band is crucial to the entire package — the ephemera I was referring to before. Each album or single cover is a black and white portrait of Morrissey’s choosing, often of actors from his beloved kitchen sink dramas of screens both big and small, but sometimes there would be an exception — a musician, a writer, a public figure of dubious fame. Before all that, while still under the impression that “Reel Around the Fountain” would be the band’s second single, Morrissey had selected a certain frame from Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus for its cover and poster campaign. Even with the change of song, the cover carried over seamlessly.

“When I thought of groups, especially in the 1970s, who constantly used female images…it was never held in question,” Morrissey said of the cover in an interview for French TV the following year. “It was just there, ‘this is rock and roll.’ But of course, it’s not. It had to be quite different. It crossed my mind that male images have never, ever been used for one reason or another, when rock and roll is obviously quite traditionally a very male sphere. So, I though it was time that they were [used], but not in a way that would exploit them.”

“Yeah, but you made a choice between Jean Marais and Clint Eastwood, for example,” the interviewer notes, tongue firmly in cheek when asking why Morrissey would choose Marais over the alpha hard-man of Hollywood. Morrissey and Marr both grin.

“Oh, most definitely,” Morrissey laughs, “and I shouldn’t have to explain why.”

The implication that The Smiths would never choose the Clint Eastwood-adjacent option presented in any situation is something I’ve delved into here, but to round out my love letter to “This Charming Man,” let’s talk about another thing (besides a sense of humor) that I immediately found in The Smiths both musically and visually, even amongst the supposedly fey and the effeminate and the romantic: a threat of violence.

I’ve written about it on multiple occasions, but I’ll say it again here, verbatim from this past newsletter:

Femininity at its core, to me, is violent. Not just because of the violence enacted on women and feminine-presenting people at large, but in the violent joy they express as well. It has almost nothing to do with outward appearance. Emotions exist in an active, brutal state. That could just be the drama of youth talking, but my creativity exists in that state too. To be truly creative is an act of beauty and anguish in equal measure. If creativity is, in fact, a traditionally “feminine trait,” why is it so bloody? So sacrificial? Why is it often so angry?

The Smiths 100% work in that lineage. My favorite opening line of all time, with pretty much no competition? “Sweetness / Sweetness, I was only joking when I said I’d like to / Smash every tooth in your head.” Written by, say, a Robert Plant or an Axl Rose, that line would read differently than it does. However, neither of them would write a line that clever, with the joke apparent. When it’s written with Morrissey’s pen and sang in Morrissey’s voice with Morrissey’s sense of humor, the line retains its edge while never tipping into, say, domestic violence territory. Fragility and brutality exist simultaneously within one complex human being: one does not cancel the other out. There’s lots to be brutal about, especially when the world doesn’t listen to a large chunk of the population they’re taught is inferior. The Smiths understand this.

When I read Morrissey’s Autobiography (maybe the funniest memoir ever published if you keep in mind that you’re dealing with an unreliable narrator), I wrote this line down from the section about his childhood: “My notepad resting on my lap takes the scribbles of unwritten truth: effeminate men are very witty, whereas macho men are duller than death.” I think something within that struck me as a funhouse mirror of my own childhood experience.

I am bewildered (in a good way) by parents now who say they adjust their behavior for the well-being of their sensitive children. “Sensitive” was thrown around like it carried the bile of a slur when I was growing up. I think about attempts made to weed that behavior out of my equally sensitive brother. Yet, I also think of temper tantrums grown men were allowed to throw in front of me, knowing that if I’d ever attempted the same thing, I’d be finished. I think about creating my own secret world in which I was allowed to flourish and create and seethe. I think about cultivating an actual sense of humor that didn’t feel the need to punch down. I think about who I still exclude from that secret world out of learned, honest-to-god fear. I think about how that fear made me angrier than even I could fathom.

The Smiths rewrote the rules for all rock bands while becoming the new platonic ideal of what a rock band should be, but also knew that emotions exist in an active, brutal state. People who didn’t feel that way had Twee Pop — no hate to Twee Pop, but this was something else. They were consciously sensitive, but never weak. The two are conflated too often. Morrissey, once upon a time, knew better.

I don’t know what the first video I saw of The Smiths was, but I have a feeling it might’ve been the Top of the Pops performance of “William, It Was Really Nothing” — again, another song probably about one man convincing another man that marriage isn’t worth it, while containing layers of ambiguity regarding the narrator’s relationship the man he’s having the conversation with. It’s also, just on a musical and melodic level, (you guessed it) a perfect song. I regard this clip as a watershed moment in my understanding of pop imagery, as well as just a great example of why I love the art form so much. It’s worth noting in every televised Smiths performance how different they look from the presenters and other performers. Part of why they’ve aged so well as an act certainly has to do with their carefully cultivated everyman appearance that belonged to no set time or place — “normcore” is the term now, I believe. Andy Rourke has told the story that the band showed up in their jeans and sweaters to perform “This Charming Man,” and the Top of the Pops people were stunned that they would actually consider going on TV wearing something that someone watching them could also be wearing.

It’s all so simple, but effective: Morrissey tearing said ordinary clothes off to reveal the giant “MARRY ME” scrawled across his chest, ready for the adoring camera to close in on him (gazing longingly at our statuesque medium of choice between worlds, knowing he is one of the few who could translate our terror and radiance) as he sings the line, “I don't dream about anyone except myself.” It’s not clear whether he’s quoting the engaged girl he’s making fun of or he’s making the statement himself, but if you’ve learned anything from what I’ve ranted about here so far, you know it’s probably both.

But back to “This Charming Man.” In pretty much every filmed promotional performance of the song, Morrissey has a giant bouquet of flowers in hand, often swinging it like it’s his weapon of choice. The performance below comes from British music television show The Tube. One thing I’d like to note about it before even touching Morrissey, armed with a florist’s battalion, is Johnny’s face being completely obscured throughout. Johnny himself wrote about it in his autobiography (which is not as well-written or entertaining as Morrissey’s but probably more grounded in fact, which is fair enough):

After some conjecture I concluded that either the director must have had some weird personal vendetta against me, or maybe, just maybe, I was considered too weird or dangerous to be on the screen. Nineteen-year-old me? Surely that was crazy. It was only years later that the mystery was finally solved, when the director admitted to a biographer that he had in fact deemed me too risqué to transmit. Apparently he thought I’d looked too drop-dead decadent for the nation’s youth to be able to cope with. I thought I looked all right.

That makes it sound like it was just because he had eye makeup on. I wouldn’t know. Do with this mystery what you will.

It’s especially strange because Morrissey was clearly the bigger threat to people’s perception of what a dangerous pop star could look like or be. This is the man who later wrote the song “Trouble Loves Me,” and in October 1983, people were going to learn just how much.

With looped strands of beads hanging down his chest and baby blue blouse hanging open, Morrissey steps through piles of petals strewn across the floor, swinging his gladioli like the whirl of a helicopter, searching to decapitate. Searching to destroy, as Iggy Pop said a decade before. “You hit me with a flower / You do it every hour / Oh, baby, you’re so vicious,” Lou Reed (one of my and Morrissey’s shared favorites) had written the year before that. He does, in fact, mime along to the song like he could become vicious at any second. He’s serious. The brow remains furrowed. He doesn’t dare crack a smile. He stares down the barrel of the lens like his story of a broken bike and a stranger’s relationship advice is a threat. And isn’t it, just a little bit?

Let’s repeat it for you to really hear, with growing intensity as each round passes: “He knows so much about these things / He knows so much about these things / He knows so much about these things.”

It’s one of those miraculous little moments where you can look nothing like the person performing, but you still feel that you see yourself reflected more clearly that you ever have before. In that moment, I saw myself a little bit: leaning down to lay against my mirror, smart and contradictory and true, living organism of a sword in hand. Not to be fucked with, the two of us. Actual violent femmes.

…..Ahaaaaaa. Don’t say I’m not good at wrapping these things up.